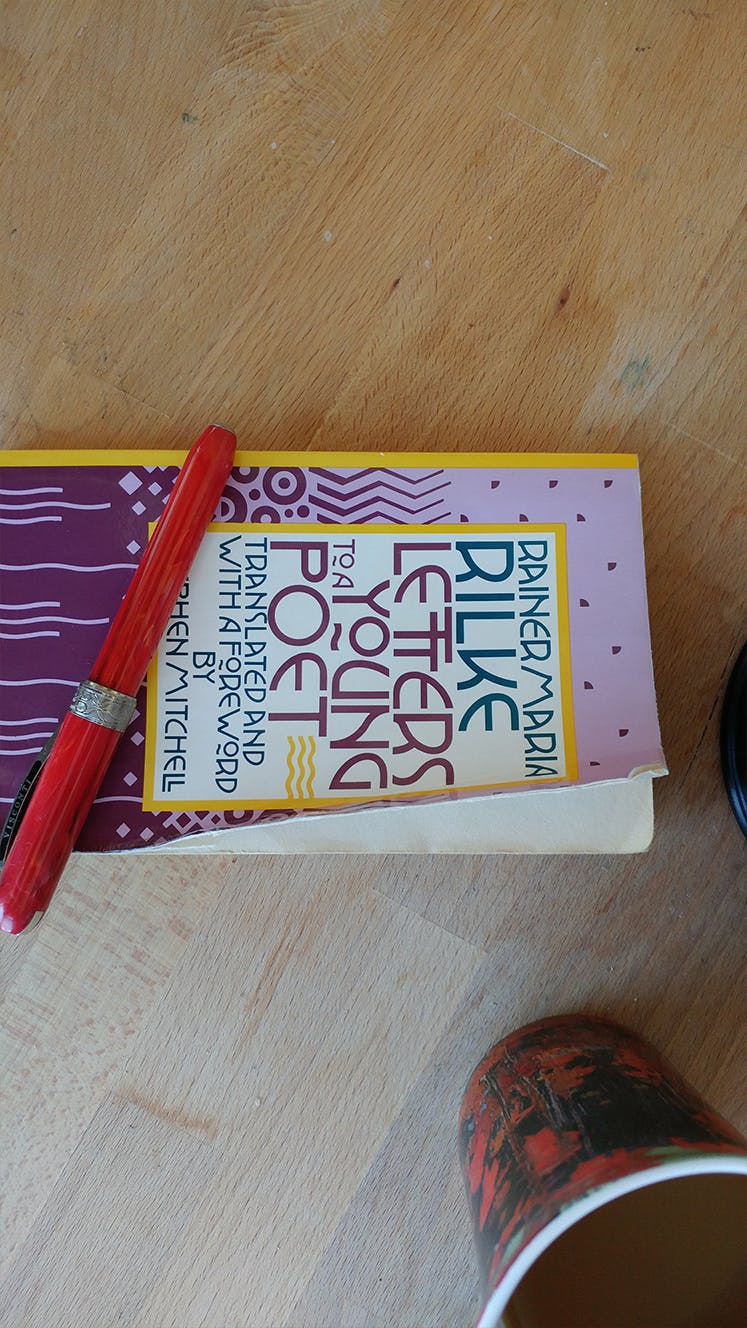

I just finished reading Letters to a Young Poet, a short collection of letters from the poet Rainer Maria Rilke to a young follower. This is a short book - a collection of a dozen letters - but it packs quite a punch.

Over the course of the hundred pages you never once hear from the young man, but through Rilke's writing you get a sense of his situation.

Rilke is surprisingly tender; it's hard to imagine a famous author taking the time to speak to his fans like this, but clearly there is something in the young man that the poet appreciates. You get the sense that Rilke is writing to a younger version of himself, and indeed that is likely the case; the two men went to the same military school and shared mutual professors. Many of the hardships that the young man (presumably) writes about are likely scenarios that Rilke would have had to deal with seven years earlier.

Life in the military does not seem easy for the young man, and Rilke does his best to confort him. The hardships of military school seem like nothing compared to the isolation of the outpost at which he is stationed. But this isolation - Rilke writes - may not be the curse the young man thinks it is.

No one can advise or help you - no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to youself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.

This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple "I must", then build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and a witness to this impulse.

In his very first letter, Rilke asks the young man to think about what writing means to him. If he were completely cut out from the rest of civilization - if all he had was his mind and an infinite amount of time to create - would he be happy? If not, Rilke writes, perhaps poetry is not the profession for him. There is no shame in that, as it's likely there must be something else.

A man taken out of his room and, almost without preparation or transition, placed on the heights of a great mountain range, would feel something like that: an unequalled insecurity, an abandonment to the nameless, would almost annihilate him. He would feel he was falling or think he was being catapulted out into space or exploded into a thousand pieces: what a collosal lie his brain would have to invent in order to catch up with and explain the situation of his senses.

That is how all distances, all measures, change for the person who becomes solitary; many of these changes occur suddenly and then, as with the man on the mountaintop, unusual fantasies and strange feelings arise, which seem to grow out beyond all that is bearable. But it is necessary for us to experience that too. We must accept our reality as vastly as we possibly can; everything, even the unprecedented, must be possible within it. This is in the end the only kind of courage that is required of us: the courage to face the strangest, most unusual, most inexplicable experiences that can meet us

Rilke's subsequent letters dive into the real meat of his argument - that solitude is required for anything meaningful to take place. The mind is an incredible tool, but it requires the right circumstances to work.

Read as little as possible of literary criticism - such things are either parisan opinions, which have become petrified and meaningless, hardened and empty of life, or else they are just clever word-games, in which one view wins today, and tomorrow the opposite view. Works of art are an infinite solitude, and no means of approach is so useless as criticism. Only love can touch and hold them and be fair to them.

Always trust yourself and your own feeling, as opposed to argumentations, discussions, or introductions of that sort; if it turns out that you are wrong, then the natural growth of your inner life will eventually guide you to other insights. Allow your judgements their own silent, undistubed development, which, like all progress, must come from deep within and cannot be forced or hastened.

The mind needs to be free from criticism, ambition, and desire for acceptance. These things confuse the creative, distance them from what their mind truly wants to make.

You get the sense Rilke wouldn't mind being in prison.

That's actually probably not too far off from the truth. While Rilke spends the majority of his time giving advice to the young man, he does admit that his life isn't exactly the glamorous one you'd expect of a young hotshot poet.

Rilke is a firm user of his own medicine, and he experiences both the joys it produces and the suffering it causes. He is a nomadic soul - nearly every letter is written from some different place. He also appears to be very poor and frequently in bad health. It's not hard to see how these circumstances could lead to a life of solitude.

Don't be confused by surfaces; in the depths everything becomes law. And those who live the mystery falsely and badly (and there are very many) lose it only for themselves and nevertheless pass it on like a sealed letter, without knowing it.

Yet when Rilke writes about the lives of common folk, one does not get the sense that there is any longing in his writing. For all its ups and downs, Rilke is a master who has found his purpose. The sacrifices it demands pale in comparison to the joys it gives him.

We don't all have to be poetic geniuses

There's a lot to learn in this short book, but my ultimate conclusion surprised me. We don't all have to be like Rilke. The sacrifices requried to become a true master at your craft are great, and - as Rilke mentions at the start of his book - there are few who decide that they are willing to sacrifice everything for it. That doesn't mean that you can't do anything to be more creative, however.

You may not choose to live the life of monastic solitude that Rilke asks of you, but you can always take steps towards it. I've decided to turn off the notifications on my computer; from now on, I'll rely on my phone. I'll try to appreciate that creativity takes time, especially now in our busy and connected world. And I'll try to live simply, removing unneccesary stresses from my life.

And if there is one more thing that I must say to you, it is this: Don't think that the person who is trying to comfort you now lives untroubled among the simple and quiet words that sometimes give you pleasure. His life has much trouble and sadness, and remains far behind yours. If it were otherwise, he would never have been able to find those words.

We can't all be Rilke, but we can still learn from him.